“The brains of people are more interesting than the looks I think,” Hollywood actress and inventor Hedy Lamarr said in 1990, 10 years before she passed.

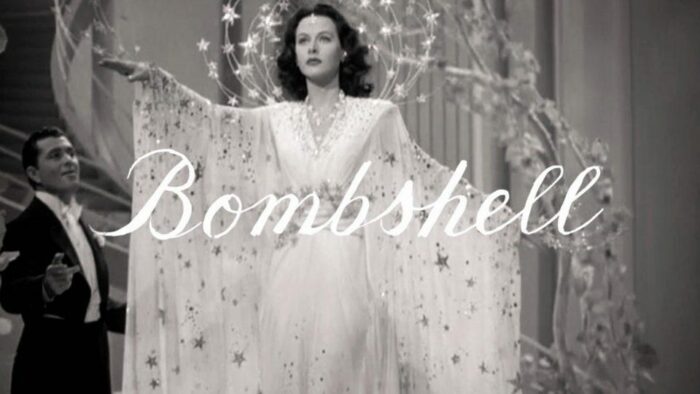

The striking movie star may be most well-known for her roles in the 1940s Oscar-nominated films ‘Algiers’ and ‘Sampson and Delilah.’ But it is her technical mind that is her greatest legacy, according to a new documentary on her life called ‘Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story.’ The film chronicles the patent that LaMarr filed for frequency-hopping technology in 1941 that became a precursor to the secure wi-fi, GPS and Bluetooth now used by billions of people around the world.

LaMarr’s life story is indeed remarkable. Born in Austria to Jewish parents, she married her first husband in 1934 at age 19. Unhappily married to an affluent, domineering munitions manufacturer, LaMarr fled their home by bicycle in the middle of the night.

She emigrated to the U.S. in the lead up to World War II and caught the eye of MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer on the ship from London to New York. LaMarr spoke little English but talked her way into a lucrative contract to act in Hollywood films. The Viennese beauty soon settled into life in Beverly Hills and socialized with luminaries including John F. Kennedy and Howard Hughes, who provided her with equipment to run experiments in her trailer during her downtime from acting. It was in this scientific environment that LaMarr found her true calling.

“Inventions are easy for me to do,’ the Austrian accented LaMarr says in ‘Bombshell.’ “I don’t have to work on ideas, they come naturally.”

What did not come naturally to LaMarr however, was the notoriety and compensation she deserved for her ideas. The patent she filed with co-inventor George Antheil aimed to protect their war-time invention for radio communications to ‘hop’ from one frequency to another, so that Allied torpedoes couldn’t be detected by the Nazis. To this day, neither LaMarr nor her estate have seen a cent from the multi-billion-dollar industry her idea paved the way for, even though the U.S. military has publicly acknowledged her frequency-hopping patent and contribution to technology.

LaMarr’s work as an inventor was barely publicized in the 1940s, an oversight that ‘Bombshell’ director and Reframed Pictures Co-Founder, Alexandra Dean, believes fits into the narrow narrative for a movie-star in those days.

“From Hedy they absolutely wanted glamour,” says Dean in an interview in New York. “They wanted somebody to stare at in the movie theaters that would help forget all their troubles.”

Professor Jan-Christopher Horak, the Director of UCLA Film & Television Archive, states in ‘Bombshell’ that MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer, who first signed LaMarr to a Hollywood contract, saw women as fitting into one of two buckets: they were either seductive, or, they were to be put on a pedestal and admired from afar. A woman being both sexy and admirable was not something Professor Horak believes Mayer was willing to accept or project to film audiences.

“Louis B. Mayer divided the world into two kinds of women: Madonna and whore. I don’t think he ever believed she was anything but the latter,” says Horak in the film, referring to LaMarr.

Dr. Simon Nyeck, the Chair of Branding at the ESSEC Business School in Paris and a previous Fellow at Harvard Business School, agrees that Hollywood categorized women in a binary way. Dr. Nyeck teaches ‘Anthropology of a Powerful Brand’ at ESSEC, and is an expert on the use of female archetypes in advertising and media.

According to Dr. Nyeck, women are positioned as one of three archetypes: The powerful, clever Queen, the seductive Princess, or the Femme Fatale who is a combination of both. He says these archetypes date back to Greek mythology and are still used to depict women in media and advertising today. Dr. Nyeck says that ‘Femme Fatale’ is the category that the beautiful, brilliant inventor LaMarr fit into, and that multi-dimensional women are often seen as very threatening.

“A powerful lady who is sexy, but smart… It is really scary for most guys,” Dr. Nyeck says. “You just expose how weak we are.”

Dr. Nyeck notes that historically, women have been positioned in the media within an antiquated, one-dimensional framework created from a male perspective. In that framework, multi-faceted women like Lamarr are often only valued for their physicality, and not for their ability to think, invent or create. That narrative about the limited capabilities of women is projected to impressionable audiences around the world.

“The position of the ladies is almost like toys,” says Dr. Nyeck. “They have no say. And that’s exactly the problem.”

Because of this, Dr. Nyeck is not surprised that LaMarr’s entrepreneurial efforts to produce and direct films in the 1940s were not encouraged. Or that it has taken decades for the narrative around Lamarr to evolve to give her credit as the inventor that she was.

“The subject of history for so long had been men,” says ‘Bombshell’ director Alexandra Dean. “And it has been men telling the story of history, they’ve been the storytellers. So, of course, the heroes with all the complexity and the drama, are men, you know. The female subject is often somebody who is just there to highlight the qualities and complexity of the male subjects.”

The Executive Director of the ACLU of Southern California agrees that Hollywood has a powerful ability to not just reflect culture but to shape it. Villagra was a panelist at the UN Women USNC L.A. Media Summit event that I chaired in May 2016. He voiced his concerns about gender discrimination in Hollywood and that there are so few female directors.

“When men are almost exclusively making film and television shows, they’re telling predominately male stories,” says Villagra. “They’re depicting women through a male lens, through a male gaze. They’re reinforcing stereotypes of women, and they’re reinforcing male privilege.”

Recent statistics support his case. Just 7% of the 250 highest-grossing US film releases were directed by a woman in 2016, according to a report from the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University. Yet the Motion Picture Association of America says that the U.S./Canadian box office generated a record-breaking $11.4-billion in 2016, and that 52% of those moviegoers were female.

The success of female-directed ‘Wonder Woman’ which brought in more than $820-million across the globe in 2017, and Disney’s ‘Frozen’ written and directed by Jennifer Lee that grossed $1.2-billion in 2013, reiterates that female directors are capable of excelling in the job.

LaMarr’s daughter, Denise Loder, is proud of her mother’s inventive mind and the work that she did throughout her career to push the boundaries of how women are perceived. She notes that her mom and Betty Davis were two of the first women to own production companies and to tell stories from a female perspective.

“She was so ahead of her time with being a feminist,” says Loder in ‘Bombshell.’ “She has never been called that, but, she certainly was.”