Lamarr was a gifted inventor as well as a screen siren—though you wouldn’t know it from Ecstasy and Me, the torrid “autobiography” that ruined her life.

I’ve never been satisfied. I’ve no sooner done one thing than I am seething inside me to do another thing,” Golden Age screen siren Hedy Lamarr once said.

And do things Lamarr did. The stunning star of classics including Algiers and Samson and Delilah was much more than the label she was given, “the most beautiful woman in the world.” Married six times, she was an actress, pioneering female producer, ski-resort impresario, painter, art collector, and groundbreaking inventor, whose important innovations are meticulously cataloged in Pulitzer Prize winner Richard Rhodes’s 2012 book, Hedy’s Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World.

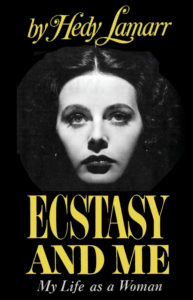

However, it was another book that would alter the course of Lamarr’s life. Ecstasy and Me: My Life as a Woman, ghostwritten by Cy Rice and Leo Guild (who was also ghostwriter of the notorious Barbara Payton tell-all I Am Not Ashamed), was released in 1966 and immediately became a best seller.

Based on 50 hours of taped conversations with the eccentric, vulnerable Lamarr, Ecstasy and Me is a grotesquely fascinating chronicle of the way women have been sexualized, minimized, and trivialized throughout history. Though it’s classified as an autobiography, the book starts with a male psychologist proclaiming that the sex-positive Lamarr is “blissfully unaffected by moral standards that our contemporary culture declares acceptable,” and goes on nauseatingly from there.

Lurid, amorous encounters right out of a Roger Corman sexploitation film and sexual trauma disguised as titillation are the main foci of this supposed autobiography, though sometimes it breaks, bizarrely, for transcripts of conversations Lamarr recorded with a psychiatrist. Sprinkled in are standard Hollywood gossip—sometimes catty, occasionally kind portraits of everyone from Judy Garland and Clark Gable to Ingrid Bergman—and inane pronouncements such as “Why Americans suspect bidets, I’ll never know. They are the last word in cleanliness.”

In 2010’s definitive Beautiful: The Life of Hedy Lamarr, biographer Stephen Michael Shearer writes that those close to Lamarr believed some of the nonsexual stories in Ecstasy and Me were accurate, with Lamarr’s own voice occasionally breaking through the sensationalist muddle. But they also felt the outlandish sexual stories were complete lies. The reader gets the sense that while Lamarr may have said the things she’s quoted as saying, statements made while she might have been high shouldn’t have been taken at face value. It’s no wonder Lamarr would sue unsuccessfully in an attempt to stop the publication of Ecstasy and Me, which she labeled “fictional, false, vulgar, scandalous, libelous, and obscene.” As she told Merv Griffin in 1969, “That’s not my book.”

Lamarr was born Hedwig Kiesler in Vienna, Austria, in 1914, to an assimilated Jewish family. In Hedy’s Folly, Rhodes paints a captivating picture of the artistic, intellectual Vienna of Lamarr’s youth, exploring the forces that would shape her (and making the reader wish they could step back in time). While Lamarr’s cultured mother worried that her extraordinarily beautiful, bright, and headstrong only child would grow spoiled, her father, Emil, a prominent banker, coddled and cultivated his precious daughter. “He made me understand that I must make my own decisions, mold my own character, think my own thoughts,” Lamarr later recalled, per Rhodes.

Ecstasy and Me describes Lamarr’s adolescence as a tumultuous time, filled with the trauma of attempted rape, lurid sexual exploits at boarding school, and an affair with her friend’s father that produced “uncountable” orgasms. It fails to mention, though, that when she was a teenager, she was already learning mechanics, and had become a fearless self-promoter and a protégé of theatrical impresario Max Reinhardt.

Ecstasy and Me describes Lamarr’s adolescence as a tumultuous time, filled with the trauma of attempted rape, lurid sexual exploits at boarding school, and an affair with her friend’s father that produced “uncountable” orgasms. It fails to mention, though, that when she was a teenager, she was already learning mechanics, and had become a fearless self-promoter and a protégé of theatrical impresario Max Reinhardt.

At the age of 17, Lamarr was cast in the film that catapulted her to international stardom and infamy: Ecstasy, the project that gave her purported autobiography its title. The movie includes a scene in which Lamarr (who was unaccompanied by her parents during shooting) swimming nude and simulating an orgasm—a first in film history. Some of the only affecting passages in Ecstasy and Me come when Lamarr describes the exploitation she suffered at the hands of powerful men while making films like these.

Most disturbing are her allegations that Ecstasy director Gustav Machatý resorted to cruel methods to get the teenager’s reactive face during her love scene with costar Aribert Mog:

Aribert took over me, and the scene began again. Aribert slipped down out of range on one side. From down out of range on the other side, the director jabbed that pin into my buttocks “a little” and I reacted…. I remember one shot when the close-up camera caught my face in a distortion of real agony…and the director yelled happily “Ya, goot!”

In 1933, Lamarr married munitions manufacturer Fritz Mandl. “He had the most amazing brain…. There was nothing he did not know…. Ask him a formula in chemistry and he would give it to you,” she said, per Rhodes.

The union was an unhappy one, though Ecstasy and Me conveniently leaves out crucial details about her relationship to make Lamarr appear blameless. That book describes her marriage as a perverse fairy tale. The much older Mandl did not allow her to act; Lamarr soon found that life with him was little more than a prison, a “gilded cage.”

All of Lamarr’s biographers agree that Mandl was insanely controlling and jealous of his wife’s beauty and infamy. Incensed and embarrassed by Lamarr’s nudity in Ecstasy, he spent a large sum of money in an attempt to buy up all existing copies of the film (he failed).

But Lamarr was not entirely as hopeless as she is portrayed in Ecstasy and Me. Shearer writes in Beautiful that while married, Lamarr had an affair with her husband’s best friend, Prince Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg. And according to Rhodes, she was far from the stereotypical trophy wife. Lamarr listened carefully to talk of the German military’s technological innovations as she presided over grand dinners in Starhemberg’s home. One of the most intriguing aspects of Hedy’s Folly is the detailed insight it gives into the big-business world of munitions and armaments, and how it may have influenced Lamarr’s future inventions.

If both Ecstasy and Me and Hedy’s Folly sometimes read more like spy thrillers than nonfiction, it is because what came next for Lamarr was incontestably dramatic. Always a fabulist, Lamarr would tell numerous stories of her attempts to flee Mandl. In Ecstasy and Me, the chosen version is particularly outrageous: that Lamarr hired a maid who looked like her so that she could steal the maid’s identity and sneak out of the house using the servants’ entrance. Lamarr’s son would corroborate this unbelievable story in the excellent, nuanced 2017 documentary Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story.

Whatever the truth, though, she did escape—first to Paris, then to London. By 1937, Lamarr was headed to Hollywood, with a contract from MGM’s Louis B. Mayer. Ecstasy and Me paints the exec as a phony, lecherous ham whom Lamarr constantly outsmarts. One can only hope that is true.

By 1940, the newly christened Hedy Lamarr was a bona fide movie star. Disdainful of the Hollywood social whirl, she preferred painting or swimming with her good friend Ann Sothern. “Any girl can be glamorous,” she later said. “All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.”

Ecstasy and Me presents these years as times of endless lovemaking and rehashes tired tropes about movie making. But according to Rhodes, Lamarr’s real passions were her inventions. She spent countless nights tinkering in a corner of her Benedict Canyon mansion, which contained drafting boards and gadgets galore. “My mother was very bright minded,” her son Anthony Loder later told the L.A. Times. “She always had solutions. Anytime someone complained about anything, boom, her mind came up with a solution.”

According to that same paper, while dating Howard Hughes, Lamarr worked on plans to streamline his airplanes. She also invented a bouillon cube that produced cola when dropped in plain water. But her real contribution to science arose out of a chance meeting with the flamboyant avant-garde composer and amateur inventor George Antheil (who is heavily profiled in Hedy’s Folly—so much that it makes the reader wish Rhodes would just get back to Lamarr’s story) at the home of movie star Janet Gaynor.

Antheil would later say that Lamarr was initially interested in his claim that he could make her breasts bigger (bosoms are a preoccupation in Ecstasy and Me as well). But the two soon turned their focus to helping the war effort, and began work on an invention based on Lamarr’s theory of “frequency hopping,” which could stop radio systems from being jammed by the enemy, aiding in torpedo launches. In August 1942, the government issued its “secret communication system,” U.S. patent No. 2,292,387. This system would later be used by the U.S. Navy and would be highly influential.

If Hedy’s Folly is sometimes bogged down by scientific and mechanical details, it is at least an overdue overcorrection. Books like Rhodes’s are a necessary revaluation of historical women’s roles as thinkers and game changers, contrasting the narrative that their lives were guided only by romance, physical appearance, and children. It is almost impossible to believe that in 50 hours of interviews, Lamarr never mentioned inventing—but in Ecstasy and Me, her passion is not mentioned once.

So why did this curious, ingenious woman agree to participate in Ecstasy and Me in the first place? By the mid-1960s, Lamarr’s movie stardom and six tumultuous marriages were firmly in the past. She claimed to be broke, and according to the documentary Bombshell, was addicted to methamphetamines (she was a patient of Max Jacobson, the notorious “Dr. Feelgood”). In 1966, Lamarr was arrested at the May Company department store in Los Angeles for allegedly stealing items including two strings of beads, a lipstick brush, and an eye makeup brush. She was later acquitted.

According to Beautiful: The Life of Hedy Lamarr, Lamarr received a total of $80,000 for Ecstasy and Me. She signed off on the manuscript without reading it, legally paving the way for its publication.

It was a grave error. The book’s torrid passages are written like classic pornography; they include tales of orgies on sets with starlets and assistant directors, sadomasochism, and a strange story of one lover who had sex with a doll that he had made to look like Lamarr while she watched in horror.

It also includes a few interesting passages discussing her role as a groundbreaking film producer, and defensive yet amusing retellings of her bizarre behavior during her divorce from millionare Texas oilman W. Howard Lee (she sent her stand-in to testify for her in court). But the sex is was what stuck.

Once Lamarr actually bothered to read Ecstasy and Me, she knew her career was done. “I was there when she read Ecstasy and Me for the first time,” TCM’s Robert Osborne recalls in Beautiful. “She was shocked by it. But that was the foolish side of her. She wanted money. They simply made up passages in that book and she allowed them to…. It was part of her capriciousness, giving away parts of her life for a book and not worrying about the consequences.”

Although presiding judge Ralph H. Nutter believed Ecstasy and Me was “filthy, nauseating, and revolting,” he ruled against Lamarr, and the book was published anyway. “The damage it did to Hedy’s career and reputation was irreversible,” Shearer writes in Beautiful. Reading it, one instantly understands why. The cool Austrian film goddess had been knocked off her pedestal, presenting herself (intentionally or not) as a self-professed “nymphomaniac” and an irrational, self-obsessed has-been who bemoans the curse of her great beauty one too many times.

Lamarr eventually moved to Florida. Unable to cope with aging, she became a recluse, obsessed with plastic surgery and pushing her doctors to innovate new techniques in the field. “Hedy retreated from the gazes of those who didn’t look deeper. She…filled her days with activities (and lawsuits) and, with the humor still intact, tolerated the rest of us,” Osborne writes in the forward to Beautiful.

Lamarr rarely saw her children or friends, but instead talked to them on the telephone for hours every day. She also claimed she was writing her autobiography, seemingly trying to erase the pain and embarrassment of Ecstasy and Me from her memory.

As Lamarr hid away, her wartime work in frequency hopping was becoming extremely important. It paved the way for Wi-Fi, cellular technology, and modern satellite systems. Lamarr was aware of these uses, and bitter that her work had not been recognized—nor had she received a cent for her contributions. “I can’t understand why there’s no acknowledgment when it’s used all over the world,” she said in an influential 1990 Forbes interview, which slowly began to wake the world up to her accomplishments.

In 1997, three years before her death, Lamarr was finally honored with the prestigious Pioneer Award from the Electronic Frontier Foundation. When she heard of the award, she said to her son simply this: “It’s about time.”

Perhaps it is fitting that it has been so hard to tell Lamarr’s entire story until recently; an extraordinarily beautiful, troubled, brilliant, sexually liberated woman has long been too much for patriarchal society to handle. This is something Lamarr seemed to understand. In a 1969 interview, she explained it to a befuddled Merv Griffin: “I’m a very simple, complicated person.”